Abdominal compartment syndrome

| Abdominal compartment syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Polycompartment syndrome[1] | |

_(cropped).jpeg.webp) | |

| Measured at the level of the vein from the kidney, anteroposterior divided by transverse abdominal diameter of over 0.8 supports the diagnosis.[2] | |

| Specialty | Critical care |

| Symptoms | Decreased urine output, hard abdomen[1] |

| Complications | Kidney failure, respiratory failure, heart failure, increased intracranial pressure, multi organ system failure[1] |

| Causes | Sepsis, pancreatitis, bleeding within the abdomen, enlarged intestines, burns, abdominal trauma, large amounts of intravenous fluids[1] |

| Risk factors | Obesity, pregnancy, high chest pressures, placing person on their front[1] |

| Diagnostic method | High Foley catheter pressure and organ failure[1] |

| Treatment | Maintain high blood pressure, gastric tube, neostigmine, laxatives, rectal tube, drain ascitis, surgery[1] |

| Frequency | Relatively common (ICU)[1] |

| Deaths | 65%[2] |

Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) is when the abdomen becomes subject to high internal pressures resulting in organ dysfunction.[1][3] Symptoms may include a swollen and hard abdomen and decreased urine output.[1][2] Among those who are intubated, ventilation becomes difficult.[2] Complications may include kidney failure, respiratory failure, heart failure, ischemic bowel, and increased intracranial pressure; ending in multi organ system failure.[1][2]

It may occur as a result of sepsis, pancreatitis, bleeding within the abdomen, enlarged intestines, burns, abdominal trauma or surgery, or large amounts of intravenous fluids.[1][2] Factors that can worsen matters include obesity, pregnancy, high chest pressures, and placing a patient on their front.[1] The underlying mechanism involves increased pressure affecting heart, lungs, kidneys, and brain.[1] Diagnosis may be supported by measuring pressures above 20 mm Hg via a Foley catheter placed in the bladder.[1]

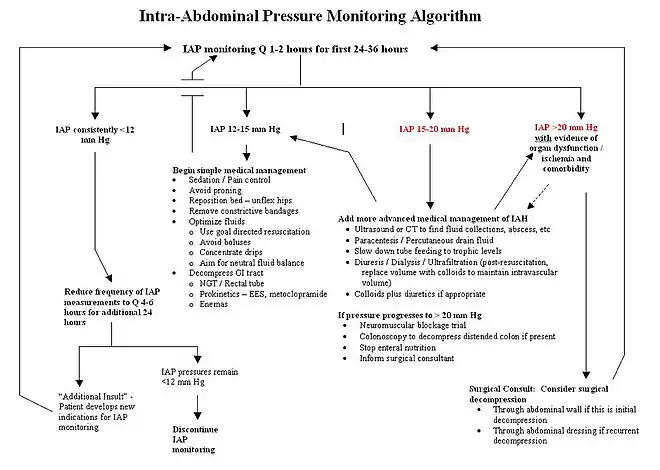

Treatment involves keeping the blood pressure sufficiently high, while limiting intravenous fluids, together with efforts to decrease abdominal pressure.[1] The goal blood pressure is at least 60 mm Hg above the intra-abdominal pressure.[1] Abdominal pressure may be decreased by placing a gastric tube, neostigmine, laxatives or a rectal tube, and draining any ascitis.[1] If this is not effective surgery to open the abdomen may be carried out.[1]

Abdominal compartment syndrome occurs relatively commonly in the intensive care unit (ICU).[1] The risk of death is as high as 70%.[2] Increased abdominal pressure was first described in 1863 Etienne-Jules Marey, with its association with organ dysfunction noted in 1873.[4] The current term came into use in 1989.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms often include decreased urine output and a hard abdomen.[1]

Complications

Possible complications include:[5]

Cause

Causes may include:[5]

- Primary

- Penetrating trauma

- Bleeding

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Bowel obstruction

- Secondary

- Peritoneal tissue edema secondary to diffuse peritonitis, abdominal trauma

- Fluid therapy due to massive volume resuscitation

- Retroperitoneal hematoma secondary to trauma and aortic rupture

- Peritoneal trauma secondary to emergency abdominal operations

- Reperfusion injury following bowel ischemia due to any cause

- Retroperitoneal and mesenteric inflammatory edema secondary to acute pancreatitis[6]

- Ileus and bowel obstruction

- Intra-abdominal masses of any cause

- Abdominal packing for control of bleeding

- Closure of the abdomen under undue tension

- Ascites (intra-abdominal fluid accumulation)[7]

- Acute pancreatitis with abscesses formation

It is classified into primary, secondary, and recurrent.[8] It may occur as a result of a primary illness or in association with treatment interventions.[9]

Pathophysiology

Abdominal compartment syndrome occurs when tissue fluid within the peritoneal and retroperitoneal space (either edema, retroperitoneal blood or free fluid in the abdomen) accumulates in such large volumes that the abdominal wall compliance is crossed and the abdomen can no longer stretch. Once the abdominal wall can no longer expand, any further fluid leaking into the tissue results in fairly rapid rises in the pressure within the space. Initially this increase in pressure does not cause organ failure but does prevent organs from working properly – this is called intra-abdominal hypertension and is defined as a pressure over 12 mmHg in adults. ACS is defined by a sustained intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) above 20 mmHg with new-onset or progressive organ failure.[10] These pressure measurements are relative. Small children can develop compartment syndromes at much lower pressures while young previously healthy athletic individuals may tolerate an abdominal pressure of 20 mmHg well. The underlying cause of the disease is capillary permeability caused by the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) that occurs in every critically ill person. SIRS leads to leakage of fluid out of the capillary beds into the interstitial space in the entire body with a profound amount of this fluid leaking into the gut wall, mesentery and retroperitoneal tissue.

Abdominal compartment syndrome follows a destructive pathway similar to compartment syndrome of the extremities. When increased compression occurs in such a hollow space, organs will begin to collapse under the pressure. As the pressure increases and reaches a point where the abdomen can no longer be distended it starts to affect the heart and lungs. There is a high mortality rate associated with abdominal compartment syndrome.[11][12]

Diagnosis

Abdominal compartment syndrome is often defined as an intra-abdominal pressure above 20 mmHg with evidence of organ failure. It develops when the intra-abdominal pressure rapidly reaches certain values and lasts for 6 or more hours. Diagnosis is generally based on intra-abdominal pressure measured most often via the urinary bladder, and it is considered the "gold standard". Multiorgan failure includes damage to the heart, lungs, kidneys, neurological, gastrointestinal, abdominal wall, and eyes. The gut is the most sensitive, and it develops evidence of damage first.[13] A review described 25 risk factors associated with intra-abdominal hypertension and 16 with abdominal compartment syndrome. These can be roughly categorized in three categories and include the role of fluid resuscitation. Large volume resuscitation with crystalloids should be avoided in those at risk.[14]

| Abdominal catastrophes | Severe organ dysfunction | Fluid balance |

|---|---|---|

| Trauma, peritonitis, acute pancreatitis, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

Often post-surgery |

Metabolic respiratory renal hemodynamic | >3000–4000 mL in 24 h window |

Treatment

The risk of death is significant at 60% to 70%. Poor outcomes relate not only to abdominal compartment syndrome itself but also to concomitant injury and bleeding.[15]

Surgery

The surgical decompression of the abdomen remains the treatment of choice if less invasive measures are not effective.[1] This is followed by one of the temporary abdominal closure techniques in order to prevent secondary intra-abdominal hypertension.[13] Surgical decompression can be achieved by opening the abdominal wall and abdominal fascia anterior in order to physically create more space. Once opened, the fascia can be bridged for support and to prevent loss of domain by a variety of medical devices (Bogota bag, artificial bur, and vacuum devices using negative pressure wound therapy).[16]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Farkas, Josh. "Abdominal compartment syndrome". IBCC. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hacking, Craig. "Abdominal compartment syndrome | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ↑ Cheatham, Michael Lee (April 2009). "Abdominal compartment syndrome". Current Opinion in Critical Care. 15 (2): 154–162. doi:10.1097/MCC.0b013e3283297934. ISSN 1070-5295. PMID 19276799. S2CID 42407737. Archived from the original on 2019-10-20. Retrieved 2022-02-05.

- 1 2 Sanda, RB (May 2007). "Abdominal compartment syndrome". Annals of Saudi medicine. 27 (3): 183–90. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2007.183. PMID 17568172.

- 1 2 Newman, Richard K.; Dayal, Nalin; Dominique, Elvita (2022). "Abdominal Compartment Syndrome". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ↑ van Brunschot, Sandra; Schut, Anne Julia; Bouwense, Stefan A.; Besselink, Marc G.; Bakker, Olaf J.; van Goor, Harry; Hofker, Sijbrand; Gooszen, Hein G.; Boermeester, Marja A.; van Santvoort, Hjalmar C. (2014). "Abdominal compartment syndrome in acute pancreatitis: a systematic review". Pancreas. 43 (5): 665–674. doi:10.1097/MPA.0000000000000108. ISSN 1536-4828. PMID 24921201. S2CID 24784362.

- ↑ Wittmann, Dietmar H; Iskander, Gaby A (2000). "The Compartment Syndrome of the Abdominal Cavity: A State of the Art Review". Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 15 (4): 201–20. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1489.2000.00201.x.

- ↑ Hunt, Leanne; Frost, Steve A.; Hillman, Ken; Newton, Phillip J.; Davidson, Patricia M. (2014-02-05). "Management of intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome: a review". Journal of Trauma Management & Outcomes. 8 (1): 2. doi:10.1186/1752-2897-8-2. ISSN 1752-2897. PMC 3925290. PMID 24499574.

- ↑ De Waele, J. J.; De laet, I.; Malbrain, M. L. N. G. (12 October 2015). "Understanding abdominal compartment syndrome". Intensive Care Medicine. 42 (6): 1068–1070. doi:10.1007/s00134-015-4089-2. PMID 26459879. S2CID 9692082.

- ↑ Malbrain, Manu L.N.G.; De laet, Inneke E. (March 2009). "Intra-Abdominal Hypertension: Evolving Concepts". Clinics in Chest Medicine. 30 (1): 45–70. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2008.09.003. PMID 19186280. Archived from the original on 2022-02-07. Retrieved 2022-02-05.

- ↑ Kirkpatrick, Andrew W.; Roberts, Derek J.; De Waele, Jan; Jaeschke, Roman; Malbrain, Manu L. N. G.; De Keulenaer, Bart; Duchesne, Juan; Bjorck, Martin; Leppaniemi, Ari; Ejike, Janeth C.; Sugrue, Michael; Cheatham, Michael; Ivatury, Rao; Ball, Chad G.; Reintam Blaser, Annika; Regli, Adrian; Balogh, Zsolt J.; d'Amours, Scott; Debergh, Dieter; Kaplan, Mark; Kimball, Edward; Olvera, Claudia; Pediatric Guidelines Sub-Committee for the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (2013). "Intra-abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: Updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome". Intensive Care Medicine. 39 (7): 1190–1206. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-2906-z. PMC 3680657. PMID 23673399.

- ↑ Abdominal Compartment Syndrome at eMedicine

- 1 2 Deenichin, Georgi Petrov (24 December 2007). "Abdominal Compartment Syndrome". Surgery Today. 38 (1): 5–19. doi:10.1007/s00595-007-3573-x. PMID 18085356. S2CID 10613413.

- ↑ De Waele, J. J.; De laet, I.; Malbrain, M. L. N. G. (12 October 2015). "Understanding abdominal compartment syndrome". Intensive Care Medicine. 42 (6): 1068–1070. doi:10.1007/s00134-015-4089-2. PMID 26459879. S2CID 9692082.

- ↑ Patel, Aashish; Lall, Chandana G.; Jennings, S. Gregory; Sandrasegaran, Kumaresan (November 2007). "Abdominal Compartment Syndrome". American Journal of Roentgenology. 189 (5): 1037–1043. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.2092. PMID 17954637.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, James EF; Gupta, Shradha; Masterson, Sarah; Sigurdsson, Helgi H (2013). "Laparostomy management using the ABThera open abdomen negative pressure therapy system in a grade IV open abdomen secondary to acute pancreatitis". International Wound Journal. 10 (2): 138–44. doi:10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.00953.x. PMC 7950789. PMID 22487377. S2CID 2459785.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- openabdomen.org Archived 2021-12-19 at the Wayback Machine

- wsacs.org Archived 2022-02-07 at the Wayback Machine